[push h=”20″]Most children have excellent sight and do not need to wear glasses. Some children may have vision screening done at school (between the ages of four and five). However, the earlier any problems are picked up, the better the outcome. If there are problems and they are not picked up at an early age, the child may have permanently reduced vision in one or both eyes. If you have any concerns about your child’s eyes, or if there is a history of squint or lazy eye in the family, do not wait for the vision screening at school. Take your child to a local optometrist for a sight test. This is free under the NHS for children under 16. Your child does not have to be able to read or talk to have a sight test.

Babies

Babies can see when they are born, but their eyes don’t always focus accurately. A baby’s eyes may squint sometimes (they may not always line up with each other), but if their eyes always seem to squint, this should be investigated. Their eyes develop gradually, and after about six weeks they should be able to follow something colourful or interesting with their eyes.

An easy test you can do at home when a baby is over six weeks old is to see if your baby’s eyes follow you around a room. If they don’t seem to be able to focus on you properly – for example, if they can’t follow you and recognise your facial gestures, or if their eyes wander when they are looking at you – it could suggest a problem. You can also try covering each of the baby’s eyes in turn. If they object to having one eye covered more than the other, they may have problems seeing out of one eye. As they get older, start to point out objects both close up and far away. If they struggle to see the objects, contact an optometrist for advice.

Long and short-sightedness

The light coming into the eye needs to be focused on the back of the eye (the retina) for you to see clearly. Some people have eyes that are too short, which means the light focuses behind the retina (they are long-sighted). This means that they have to focus more than they should do, particularly on things that are close up. Other people have eyes which are too long, so the light focuses in front of the retina (they are short-sighted). This means that they cannot see things clearly if they are far away from them (such as the TV or board at school). Both conditions can run in families.

Astigmatism

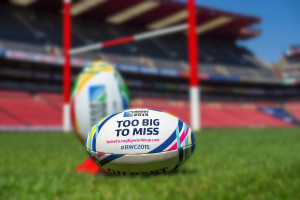

If your eye is shaped more like a rugby ball than a football, light rays are focused on more than one place in the eye, so you don’t have one clear image. This may make it hard to tell ‘N’ from ‘H’, for instance. Glasses which correct this may make a child feel strange at first, although their vision with the glasses will be clear.

Lazy eye and Squint

About 2% to 3% of all children have a lazy eye, clinically known as ‘amblyopia’. This may be because they have one eye that is much more short- or long-sighted than the other, or they may have a squint (where the eyes are not lined up together). If you notice your child appears to have a squint after they are more than six weeks old, you should have their eyes tested by an optometrist as soon as possible. The sooner the child is treated, the more likely they are to have good vision. If a lazy eye is not treated before the child is aged seven or eight, the child’s vision may be permanently affected.

The NHS recommends that all children should have vision screening during their first year at school. This is done at school and is important because many children will not realise that they have a lazy eye, and parents may not be able to see it. If your child misses the school screening for any reason, you should take them to your local optometrist for a sight test (paid for by the NHS). Don’t expect your child to tell you if there is a problem. Children assume that the way they see is normal – they will never have known anything different.

The treatment will depend on what is causing the lazy eye.

- If it is simply because the child needs glasses, the optometrist will prescribe these to correct sight problems.

- If the child has a squint, this may be fully or partially corrected with glasses. However, some children may need an operation, which can take place as early as a few months of age.

- If the child has a lazy eye, eye drops or patching the other eye can help to encourage them to use the lazy eye to make it see better.

Whether a child needs glasses or not is because of the shape and size of their eyes. Wearing glasses will not change their eye shape, and will not make your child’s eyes worse. If your child has a lazy eye, wearing glasses may make their sight permanently improve. Your optometrist will tell you how often and when your child should wear their glasses.

Which children should be tested?

You should make sure your child’s eyes are tested if:

- Your child has special needs – children with special needs often have eye problems

- There is a history of a squint or lazy eye in your child’s family

- People in the family needed to wear glasses when they were young.

Signs to look out for:

- One eye turns in or out – this may be easier to spot when the child is tired.

- They rub their eyes a lot (except when they are tired, which is normal).

- They have watery eyes.

- They are clumsy or have poor hand and eye co-ordination.

- Your child avoids reading, writing or drawing.

- They screw up their eyes or frown when they read or watch TV.

- They sit very close to the TV, or hold books or objects close to their face.

- They have behaviour or concentration problems at school.

- They don’t do as well as they should at school.

- They complain about blurred or double vision, or they have unexplained headaches.

Simple treatments like wearing glasses or wearing a patch for a while could be all that your child needs. The earlier that eye problems are picked up, the better the outcome will be. If flash photographs of your child show a white, yellow or orange colour in their pupils, or red eye in only one eye, not both, you should ask your optometrist for more information. These could be signs of a very rare but serious condition.

Colour Blindness

Around one in 12 men and one in 200 women has some sort of problem with their colour vision. If you suspect that your child has a colour-vision problem, or if there is a family history of colour-vision problems, ask your optometrist about it. There is no cure, but you can tell your child’s teachers, so that they use colours appropriately.

Protect your child’s eyes from the sun

There is evidence that too much exposure to the sun’s ultraviolet (UV) rays can contribute to the development of cataracts and age-related macular degeneration. Because children tend to spend a lot of time outside, it’s important to protect your child’s eyes in the sun. Make sure your child’s sunglasses have 100% UV protection and carry the British Standard (BS EN 1836:2005) or CE mark.

You can also protect your child’s eyes by making sure they wear a hat with a brim or a sun visor in bright sunlight. However, scientific studies have shown that children who spend time outdoors are less likely to be short-sighted, and some eye problems are linked to unhealthy lifestyles. So don’t stop your child exercising outdoors – just make sure their eyes are properly protected.

For more information or to book a children’s eye test with one of our leading optomestrists please call 01933 279203.